In the Hungarian town of Vác, an ancient church in the neighbourhood was replaced by a milestone in science for more than 200 years.

An ancient Dominican church was demolished in 1994 in the Hungarian town of Vác. When the graves inside the sacred site were opened, experts were shocked to find the preserved remains of 265 individuals.

The mummies in this case were not ordinary, but amazing mummies. Moreover, they were affected by a disease that, back in the decade, was used to remove teeth. This disease was called “tuberculosis bacillus” and was only discovered by the researcher Robert Koch in 1882. The disease is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and primarily affects the lungs, causing prolonged cough, phlegm and fever. However, people in the 18th century did not know its cause.

One third of such individuals died of the disease, for unknown reasons. It was reported that 90% of the mummies were affected by tuberculosis, even though the patients did not know when they became ill.

And, since the remains were in an excellent state of preservation, this allowed scientists to make a very important discovery for science: it will be possible to understand the evolution of the disease over the centuries.

Tuberculosis affected an entire family, which was discovered among the mummies in the pits.

They were the Hausmanns: There was the body of the eldest, Terézia Hausmann, who died at the age of 28, on December 27, 1797; and also the doll’s mother, whose name was unknown; and the younger sister, Barbara Hausmann, whom Terézia cared for.

The third, however, died of tuberculosis. Terézia was four years later, also ill and watching her mother and sister die.

What was very useful, however, is that the deaths occurred at a time close to the era of the invention of antibiotics, meaning that the bacteria had not yet adapted to the drugs.

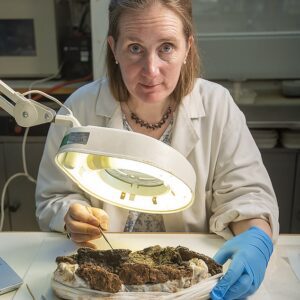

According to a report in Examene magazine, forensic anthropologist Ilidkó Szikóssy of the Hungarian National History Museum viewed the discovery as an opportunity for the development of new medical research guidelines, which could be used by doctors in medicine.

According to a report in Examene magazine, forensic anthropologist Ilidkó Szikóssy of the Hungarian National History Museum viewed the discovery as an opportunity for the development of new medical research guidelines, which could be used by doctors in medicine.

In an interview, the specialist also said that at that time there were several strains of the disease, which coexisted at the same time. When analyzing the DNA of the mummies, they found traces that originated in the Roman Empire. Only the mummies of the Hausmann family, for example, had two different types of bacterial tuberculosis.

The discovery was published in the journal Nature Communications. “It was fascinating to see the similarities between the sequences of the tuberculosis genome that were recovered and those of the genome of a recent strain from Germany,” said Mark Pallen, professor of medical microbiology at Warwick Medical School in the United Kingdom, in a statement.

The discovery was published in the journal Nature Communications. “It was fascinating to see the similarities between the sequences of the tuberculosis genome that were recovered and those of the genome of a recent strain from Germany,” said Mark Pallen, professor of medical microbiology at Warwick Medical School in the United Kingdom, in a statement.

According to Pallen, the study could help track the evolution and spread of microbes. It also “revealed that some [tuberculosis bacteria] strains have been circulating in Europe for more than two centuries,” he said.

In order to preserve the remains, the bodies had been placed in the Hungarian church between 1730 and 1838, thus allowing their preservation. It also helped, in the 1780s, that Joseph II of Austria banned burials in crypt churches, where bodies were placed one on top of the other, which was increasing pollution in the region.

However, residents of Vác did not respect the burial ban. For cultural reasons, they went to the Hungarian church and placed several important bodies underground. Until, in 1838, the practice was finally stopped.

The small corpse was then dug up in a manner similar to that of a human. However, the time the corpse was kept in, which varied between 8 and 11 days, and its high humidity of 90%, allowed the formation of a natural doll that was close to intact, allowing the detection of bacterial tuberculosis.

The mummies were transferred to the National History Museum in Hungary. According to the World Health Organization, tuberculosis, which killed millions of people every day in the world, according to data from 2019.

The answer to new TB treatments may lie in pharmacobiology, the fascinating study of how microbes acted in the past.